Letters to a Young Poetess: interview with Penny Goring

“I fear there is no god. I know there is no god,” reads a lo-fi video poem by London-based artist and poet Penny Goring in her first solo institution exhibition at ICA London, UK (9 June – 18 September 2022). “I fear this,” it continues, drawing me into its strange yet familiar world. It's Penny World, and I want more of it. I devour her collection of poems, Fail Like Fire (Arcadia Missa, 2022), in one sitting, but hunger persists. In a desperate attempt to fill myself with more of her words, I reach out to Goring, and the email conversation we end up having, like a poem, takes shape over time.

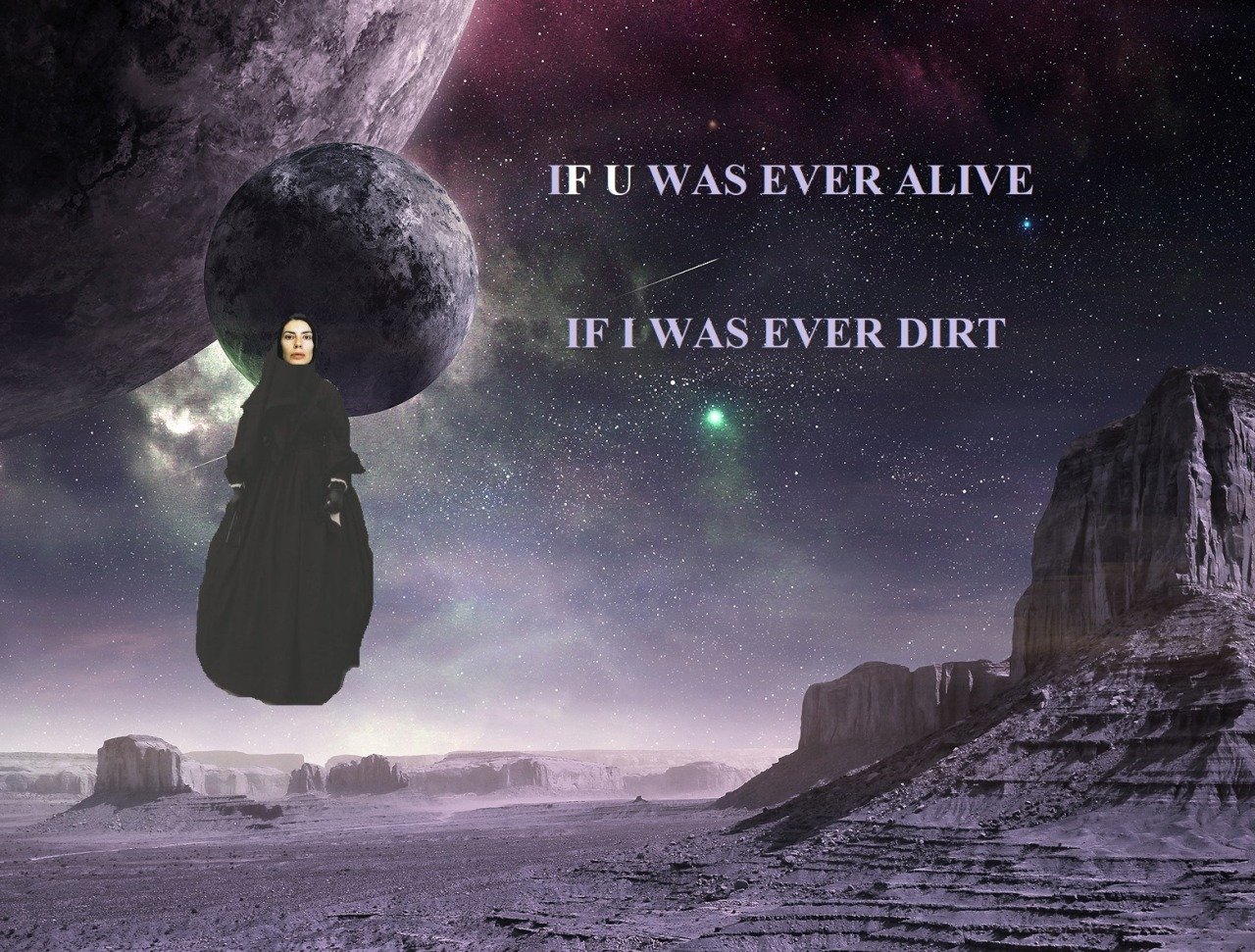

F U, 2022

NS: Penny, you’re not just one of my favourite artists but also one of the poets I look up to the most, and Fail Like Firehas been on my bookshelf since I saw your show at the ICA. How did your relationship with poetry begin?

PG: As a child growing up in the 60/70s, focusing on the lyrics of songs, playing my favourite records repeatedly and singing along, immersed in their worlds, stuff like David Bowie, Janis Joplin, Bob Dylan, and Velvet Underground. Then for my 10th birthday, one of our lodgers gave me a book of poetry titled The Mersey Sound – Adrian Henri, Roger McGough, and Brian Patten. Oh, how I loved that book - it showed me that there are no rules. I used to carry it with me and enthusiastically read the poems to my unimpressed friends. The copy I had was also the original UK paperback. I recently discovered it had mysteriously disappeared from my bookshelves and have replaced it with the Penguin Modern Classics Restored 50th Anniversary Edition.

Its original cover had a bubble-writing font; it was a craze in the 60/70s. As kids, we practised and perfected it on the covers of our school exercise books and everything. It's still my fave font for titles etc. I use it on my Tumblr, and we used it for the title of my ICA show.

NS: What does your writing process look like now?

PG: I'm not focused on writing right now. But as always, it comes out longhand in my sketchbooks alongside the drawings I make – I write anything I need to let out: angry tirades, complaints, desperate wailing, broken words, wishes, dreams, curses, shopping lists, and I make lists of words I like. I can always go back to my sketchbooks and use these word dumps to write new poems.

NS: I often think of writing poetry as an act of bravery. Do you ever feel like holding some things back when writing? Is there such a thing as being too vulnerable?

PG: I've got confused thinking about this subject, and I'm still unsure what I think about it. But this is what I wrote last week:

I don't think of it as bravery. I don't hold anything back because I don't have to, and it doesn't make me feel vulnerable. It's my way of surviving this life, the only place where I can say what I like, an outlet. It feels like my sketchbooks and first drafts are where the vulnerability happens. But then I turn it into... something else. I'm not going to say art because that sounds pretentious.

When you take something deeply personal and turn it into something else via art/artifice, the process forms a wall that protects you. Like, I'm taking my garbage and turning it into something I value that can exist entirely without me; I've designed it to be a thing apart. I use my words as raw material, then I shape, cut, hone, carve them into their own shape, make them into patterns, give them rhythm, or anything else they need to function, then maybe leave it for a few years, then edit again. Maybe, when a poem is finished, anything that began as vulnerability is subsumed? Like, you take shit and turn it into flowers.

This I wrote yesterday:

The two ‘Ornamental Onion’ poems are menopause poems, and I now see them as a bit vulnerable. When I wrote them, I was experiencing intense hormonal surges that were physically and emotionally overpowering, and in the grip of that, I had to pour it out. I don't think I could or would write like that now; they're operatic and a bit cringe. I love them as relics from a bomb blast. The menopause was a long traumatic journey, and I've come out the other side in a new relationship with my body – it left me with zero sexuality and grateful that I'm in no bodily pain. It took longing and desire out of the centre of my life. I vividly remember those feelings, but there is a distance now and room for reflection and mourning.

This today:

In life, honesty can make you vulnerable, but poems are not life, thankfully.

Forever Doll (Liar/Liar), 2021.

NS: Is your poetry in conversation with your visual language? Does one affect the other, or do they exist as separate entities?

PG: It all happens simultaneously: I see the images, I hear the words, I feel it all - in a continuous overwhelming disturbance in my body and brain. If I don't use it all, it gets too loud, and I'm in danger. If I constantly create stuff, it stops my brain from exploding. On the other hand, I've discovered that if I talk about my work a lot rather than making it, everything goes further away from me - there's an empty chasm to cross to get back into that place. And it feels like brain death. It scares me to be that out of touch with my inner life. Also, talking about my work feels like prodding a mysterious process with sharp dry sticks - it does damage. It's better left to speak for itself. That's why I make it because talking about it won't do. The conversation is the one method of communication I struggle with; the process is where I live, and the result is what leaves me – it's what I need to 'say', and it's how I want to say it.

NS: And finally, how do you know that your work, no matter its medium, is finished? Do you ever come back to it after some time has passed?

It varies, but mostly I won't stop working on something until it's done, and it's not done till nothing about it annoys my eye. I live with them for as long as possible before I know I love them enough to let them go. I used to go back and alter finished sculptures, but I can't do that these days because when something leaves my home, it gets photographed and inventoried. Also, if it gets sold, I can't pop around to someone's collection and say, Hi, I'm going to unpick this doll's eyes and cut off her legs, she'll look much better I promise, okay? This has forced me to ensure I've reached the end of my process with every work.

It's the opposite with writing, I will edit for years if I want to, and even if something is published, I can still re-write it if I feel like it. For example, I've already changed one line in ‘A for Futile’ (it's in Fail Like Fire), so when I performed it last week, I sang the new line. I'm still not entirely satisfied with that line, so no doubt it will one day change again.