Nankid, playwright Nell Leyshon interviews artist Lily Cheetham

Nell Leyshon: Can you talk about the word nankid and your understanding of it?

Lily Cheetham: It's a term for someone who is brought up by their grandparents. They have one foot in the modern world and one in their grandparents' world and I guess that is what I am. I noticed my cultural reference points were different to other people of the same generation. In the process of making my work and patchwork, I notice more and more the things that my Nana has taught me. All this work encapsulates a lot of my nankid life. My Nana brought us up and I’ve been exposed to the creative things she’s been into as well, like sewing.

My Nana’s father was a patchworker. There are some amazing quilts in the family. They are beautiful things that have been handed down by each generation. All handmade, all tiny hand-sewn stitches. Before he did patchwork, he was a doctor, specialising in caesareans. That's why his stitching was so neat - he had been stitching up women's wounds for many years. It’s an interesting transference of skills that you might not expect. I really like that.

There are a lot of artists in my family. My great grandparents were both artists on one side of my family. In the extended family there are writers and artists, also crafts like thatching and goldsmithing.

NL: Looking at our wider family, I was thinking a lot about families and artistic freedom and a lot of people get artistic freedom from leaving their family, they have to create this artistic freedom against their family in a way and they’re not understood. I think it’s quite unusual to be understood as an artist within your family.

LC: It is really unusual and I feel really lucky. But growing up I didn’t feel quite like that. My dad is from a working class background, he didn’t really understand it. So, although I knew the wider family really were more interested, I’m not sure I felt it exactly as a kid. But Nana bought me art materials and took me to see ‘Sensation’ Saachi’s exhibition in London, I don’t know many grandparents that would have been that astute. She also took us to see the Turner Prize and we went to see Tracey Emin’s bed. She had an interest in art and saw the value in it, which I think my dad was more sceptical about at the time. But she got it. My work feels like it's drawing in connections from my whole family.

NL: Can you talk a bit more about what the patchwork is?

LC: We wanted to make a letterpress book of my great grandparents' work, Norman Janes and Barbara Greg. John Grice, a local letterpress printer knew of their work and had an artist friend who owned and still used Norman’s tool handles with his initials on. I had recently inherited their life works, so we got the original woodblocks out and he taught me how to print some of them. Then he made a limited edition book. Recently he gave me all the misprints and I've used them to make the paper patchwork piece, Nankid. It's called a pineapple pattern, it’s lots of strips of paper, that butt up against each other and are sewn just like you would fabric. I’ve used fragmented parts of the images that were included in the book. I put painted lettering on top. I’ve always been interested in sign writing as an art form because it echoes back to another traditional skill. It's always had that hand drawn feel. I’ve just drawn them out on paper and used copper tape for shadowing and I like the precision and the way you can make lettering pop.

NL: There’s a huge amount of craft in all your work, isn't there?

LC: Maybe it’s something innate in me that likes things such as pattern and colour. Having worked in the art industry, especially with contemporary art, I’ve kind of got really bored of minimal work that’s highly conceptual on white walls. It just leaves me cold and I think my work is a bit of a reaction against that. The craft element for me shows the hand to the fabric or paper and the absolute connection between artist and the work. You can see it’s hand-sewn. You know it’s hand sewn. It’s not a manufactured thing that’s outsourced.

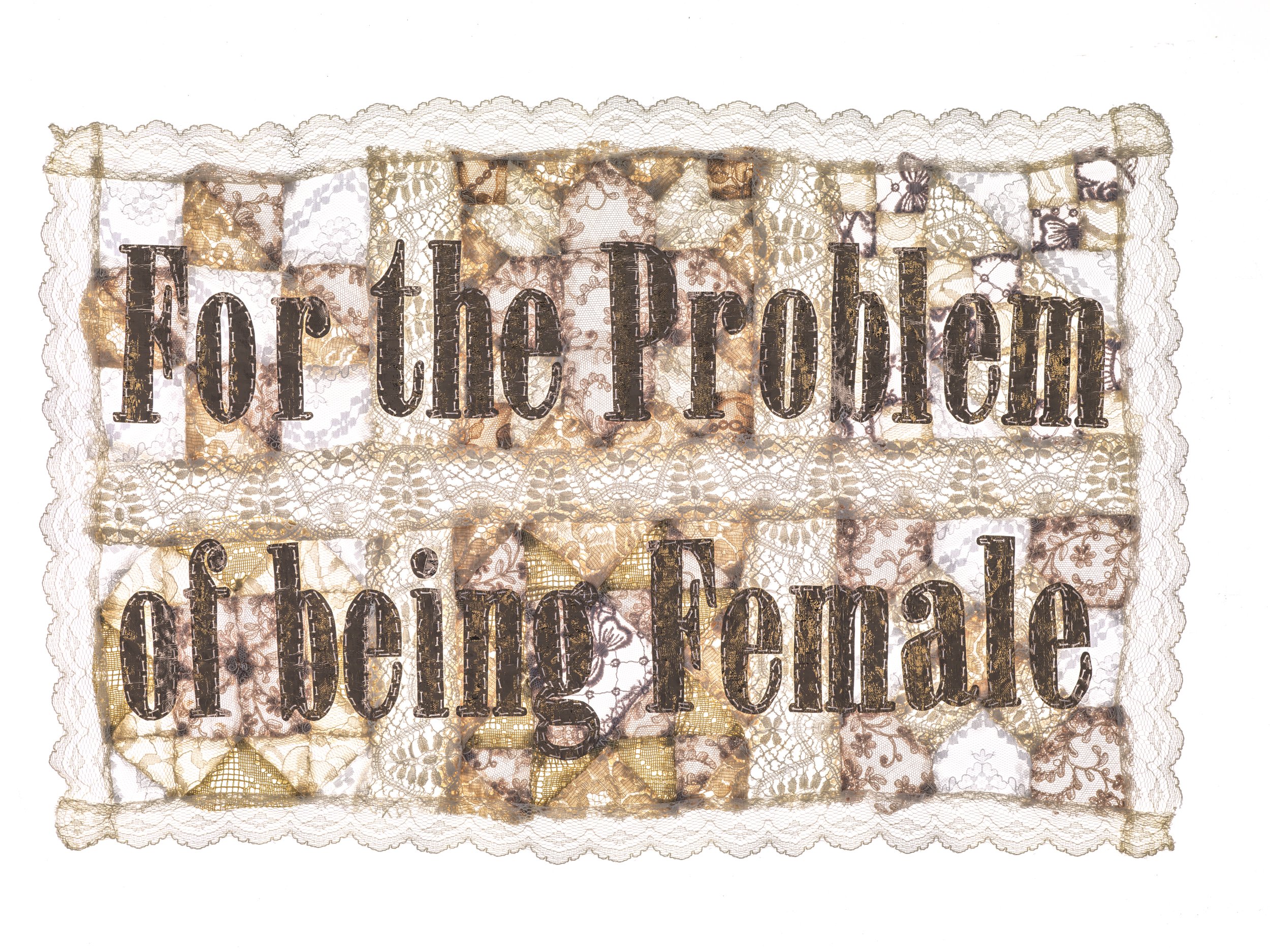

For the problem of being female, 2023 (hand sewn inherited lace patchwork), 300 x 250mm

NL: I think the same of writing. Sometimes it seems like a slog, but there is so much craft behind it, even with the smallest pieces. I notice the huge similarities to what you produced when you were living with me after art college and I can see a thread that runs all the way through.

LC: I kind of kick myself sometimes, why didn’t I have this energy and period of creativity years ago, but I wouldn’t have made the same work then. You have two, three years at university to have a go at it and it doesn’t even touch the surface. It takes a long time to work out why you need to make work and what that work should be.

NL: You can only do it when it’s the right time. You have to wait for the impetus.

LC: You’ve got to be in the headspace for it and when it comes it’s the best feeling. It’s obsessive and you want to do it all the time. Although when it isn’t there, you do just have to work through it and hope it returns.

NL: What about the difference between art or craft? Which do you categorise your work as?

LC: I think they’re the same thing. I wonder if art is a word we use to elevate some kind of work. I think a lot of it is snobbery. Everyone likes something different, so if something means something to you, or really appeals to you, then there’s something behind it and it could be classed as both. Essentially, I believe craft and art are the same, if the ideas behind it are strong.

NL: Do you feel you are subverting some of the craft tradition? Because obviously some of the pieces are playing with those very ideas.

LC: I think I am. It was never something that I intended to do, but I know for me, to say something different, you do have to put a twist on it. And that’s the thing I’m always looking for. To put a twist on it or to introduce humour or something else that does subvert it. I’m finding something that appeals to my own sensibilities. It takes confidence to do that.

NL: Why does it take confidence?

LC: When I was doing some of my earlier work I think I was afraid to use colour for example and that was down to lack of confidence but now my colour-obsessed brain just knows instinctively how to put colours together. If I like a fabric or colour I’ll use it. It’s about what sits right in my eyes. You make it for yourself.

NL: I agree. I’ve always said the more you dig into your own artistic ideas, vision and voice the more people like it anyway.

The Menopausal Shrew, 2022 (vintage fabric patchwork, hand quilted and embroidered lettering)

Series of 4 Fabric Patchwork, embroidery, 550 x 420mm (each)

LC: My work has been very personal in the past, using family letters and photographs. And I guess I wanted to put it on a wall at some point but would think why would someone be interested in something that’s so close to only my experience? But actually, it can be universal in its appeal. The minute you have an interesting title or small caption about the work, it adds an extra layer to it. It gives another way of looking at it.

I think my work used to be coded. The only way I could deal with putting something so personal on a wall was by breaking it up. Cutting bits of text up and that way it becomes slightly abstract. It would be little insights into what I’m doing, but as I’ve come along, I’ve decided not to care.

NL: What do you mean by you don’t care?

LC: I can’t just sit in my room and make art. And I’m not an outsider artist who only needs to do it just for my own wellbeing, although it does help a lot. Now I just decided that if it’s worth doing for me, then someone else will see that in the work.

NL: That’s a big shift, isn’t it?

LC: Completely. It really is therapeutic in such a subtle sort of way, to me at least. You can channel thoughts, feelings and ideas and it’s a way of exploring ideas that are on your mind. The thing about cutting up the patchwork into fragments and being happy to show those, it feels like it’s building up into a bigger picture by building up those fragments. It's feels both literal and metaphoric.

NL: What are the narratives you’re adding into your work?

LC: Feminism comes up a lot. It’s something that’s important given the connection with women's history and fabric, so if that comes out in my work then that’s great. I’ve had really positive feedback in my work, people saying they’ve seen other artists explore similar narratives but not in the way that I do.

NL: There's such a focus on women and then you have an absent woman, your own mother, and the great-grandfather who began the quilting. There’s something incredibly rich there.

LC: It’s about connecting things. I like to look for connections. Whatever I make, it’s never just flat. Even though it might look decorative and sometimes gaudy, there’s always more to it. I’ve used fabric in some works that is from my Nana’s wedding dress. The actual materials I'm using have an emotional weight in history for me. I’ve read a lot about fabric history in the last few years. If you needed to keep warm and you didn’t have much, you would make a quilt from whatever you had. You wouldn’t waste anything.

In the southern states of America, they would make ‘memory quilts’, it was a communal thing they did together. I read this one book, about one quilt that was made by a woman from her deceased husband’s clothes. It’s literally him in a quilt and for her this was a big part of the grieving process. Even the fabric would smell of him. They needed these quilts too, so it wasn’t just a pastime. I’ve found that people light up when they find a connection in my work, or notice something that’s passed down through the family. It gets bigger and bigger and more interesting when you create things using these threads of ideas.

NL: And your pieces are definitely art, not meant to be covers on a bed?

LC: Definitely art for me and that’s part of the subverting. Although I do see the artistic value in a functional beautiful handmade quilt by a grieving woman in the same way. They are just as deserving of gallery space as any great painting.

NL: I wanted to ask you about your interest in tradition and folk tradition. Obviously, you’re a Morris dancer and Boss Morris is subverting the Morris dancing model while following tradition.

LC: Boss Morris is a Morris dancing group/side, all women, set up by my amazing friend Alex Merry and her sister Kate in 2015. We’ve been Morris Dancing Cotswolds tradition, but we’ve tried all sorts of things. We do remixes to contemporary music and dance at festivals. Alex does incredible workshops and we are making an impact on the scene and hopefully trying to bring new people into it in a completely revitalised way. Recently we even danced live on stage at The Brit awards for the band Wet Leg. I never thought Morris dancing could be on a platform like that.

My work and the dancing are completely interconnected. One feeds off the other. We all work together on Boss and it’s the most incredible collective creative outlet. They are the most amazing, talented, creative people. It feeds my interests. As a group of people we’re not tied to any one tradition, we’re still really engaged with the history and the tradition, but we’re interested in making it our own.

We’ve worked with Jeremy Deller and danced at the Southbank Centre. We were also in the Radical Landscapes exhibition at the Tate Liverpool. This exhibition was about protest, landscape and the relationship to land and art. It was really interesting because it wasn’t high art and it had work chosen by people who worked for the Land Workers Alliance and protest movements. It was great to be involved with it.

NL: For me the Morris dancing nankid says so much about you and it’s also incredibly contemporary.

LC: Maybe it’s the best combination: a foot in the past, a foot in the present. Since Covid people have been looking for more. Life can be very busy and consumer-led and sterile. Fewer people have religion. When we dance, it’s not religious as such, but it has that idea of tradition and the past and ritual. We organised a May Day performance on our local common in Stroud, Gloucestershire this year and hundreds of people turned up. It was incredible and felt ceremonial. Grayson Perry has talked about loss of ritual as we have become more of a secular state and I think things like Boss fill in those gaps, but it’s also fun, it’s not loaded with certain rhetoric and the weight of the past, it’s all the best parts of ceremony and tradition. We’ve all learnt things from parents and grandparents, it has shaped us, so when we see something that has a little nod to that, it really draws people in.

NL: Can I ask, do you think about your absent mother when you make the work?

LC: Sometimes, but it’s very abstract. It creeps in. But it’s more about what could have been or what could be. I don’t have much memory of her because I was so young when she died. It’s more about what things could have been if she was still here. We might not have got on.

Widow, 2020 (stained glass, nana's wedding dress lace), 535 x 540mm

NL: So, what you’re actually stitching is possibilities?

LC: Perhaps. Or reflections. The last exhibition I did was called taught memories. The idea is the stories you are told during childhood and the memories you have become very mixed. Sometimes you don’t know what’s remembered and what’s a taught story. Your memory is so fallible. It’s amazing what your brain decides to remember or cut out.

The thought of working on a white canvas scares me but I like the process of pattern making. You decide a design and work it through and you make your decisions as you go along. It’s not copying a pattern out of a book or anything. I learn what I need to in order to make the things I want to make. Whether that’s patchwork or paper patchwork or stained glass, I learn how to do it. But there is always a theme of pattern and the ideas that underpin it. I think there’s a sense of order and satisfaction of things being in line or formation and that's why humans get so much pleasure from it.

NL: What makes you do it? And what’s next?

LC: Since Covid, it's kept me going and means I’m very busy with fitting in the rest of life too. But now something has changed and I realise I have to do it. Before Covid, I used to have this worry and guilt that it was an indulgence because I had a day job and responsibilities. But if I don’t have it now, I know the work won’t make itself, so I’m just going to continue making work and push things further, do more exhibitions and find the things and opportunities that scare me and do them anyway.

Piecework by Lily Cheetham, 27 OCT - 05 NOV at Weven, Stroud, UK

https://weven.co.uk/events/piecework/

Lily Cheetham is an artist who works with textiles and mixed media. She comes from a long line of patchwork quilt makers and has worked for many years in the contemporary art world. She is also a dancer with Stroud Morris dancing side Boss Morris.

Nell Leyshon is a playwright and novelist. Her play FOLK was performed at Hampstead Theatre and BBC Radio 3.